Inductive dimension

In the mathematical field of topology, the inductive dimension of a topological space X is either of two values, the small inductive dimension ind(X) or the large inductive dimension Ind(X). These are based on the observation that, in n-dimensional Euclidean space Rn, (n − 1)-dimensional spheres (that is, the boundaries of n-dimensional balls) have dimension n − 1. Therefore it should be possible to define the dimension of a space inductively in terms of the dimensions of the boundaries of suitable open sets.

The small and large inductive dimensions are two of the three most usual ways of capturing the notion of "dimension" for a topological space, in a way that depends only on the topology (and not, say, on the properties of a metric space). The other is the Lebesgue covering dimension. The term "topological dimension" is ordinarily understood to refer to Lebesgue covering dimension. For "sufficiently nice" spaces, the three measures of dimension are equal.

Contents |

Formal definition

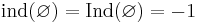

We want the dimension of a point to be 0, and a point has empty boundary, so we start with

Then inductively, ind(X) is the smallest n such that, for every  and every open set U containing x, there is an open V containing x, where the closure of V is a subset of U, such that the boundary of V has small inductive dimension less than or equal to n − 1. (In the case above, where X is Euclidean n-dimensional space, V will be chosen to be an n-dimensional ball centered at x.)

and every open set U containing x, there is an open V containing x, where the closure of V is a subset of U, such that the boundary of V has small inductive dimension less than or equal to n − 1. (In the case above, where X is Euclidean n-dimensional space, V will be chosen to be an n-dimensional ball centered at x.)

For the large inductive dimension, we restrict the choice of V still further; Ind(X) is the smallest n such that, for every closed subset F of every open subset U of X, there is an open V in between (that is, F is a subset of V and the closure of V is a subset of U), such that the boundary of V has large inductive dimension less than or equal to n − 1.

Relationship between dimensions

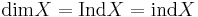

Let  be the Lebesgue covering dimension. For any topological space X, we have

be the Lebesgue covering dimension. For any topological space X, we have

if and only if

if and only if

Urysohn's theorem states that when X is a normal space with a countable base, then

.

.

Such spaces are exactly the separable and metrizable X (see Urysohn's metrization theorem).

The Nöbeling-Pontryagin theorem then states that such spaces with finite dimension are characterised up to homeomorphism as the subspaces of the Euclidean spaces, with their usual topology. The Menger-Nöbeling theorem (1932) states that if X is compact metric separable and of dimension n, then it embeds as a subspace of Euclidean space of dimension 2n + 1. (Georg Nöbeling was a student of Karl Menger. He introduced Nöbeling space, the subspace of R2n + 1 consisting of points with at least n + 1 co-ordinates being irrational numbers, which has universal properties for embedding spaces of dimension n.)

Assuming only X metrizable we have (Miroslav Katětov)

- ind X ≤ Ind X = dim X;

or assuming X compact and Hausdorff (P. S. Aleksandrov)

- dim X ≤ ind X ≤ Ind X.

Either inequality here may be strict; an example of Vladimir V. Filippov shows that the two inductive dimensions may differ.

A separable metric space X satisfies the inequality  if and only if for every closed sub-space

if and only if for every closed sub-space  of the space

of the space  and each continuous mapping

and each continuous mapping  there exists a continuous extension

there exists a continuous extension  .

.

References

Further reading

- Crilly, Tony, 2005, "Paul Urysohn and Karl Menger: papers on dimension theory" in Grattan-Guinness, I., ed., Landmark Writings in Western Mathematics. Elsevier: 844-55.

- R. Engelking, Theory of Dimensions. Finite and Infinite, Heldermann Verlag (1995), ISBN 3-88538-010-2.

- V. V. Fedorchuk, The Fundamentals of Dimension Theory, appearing in Encyclopaedia of Mathematical Sciences, Volume 17, General Topology I, (1993) A. V. Arkhangel'skii and L. S. Pontryagin (Eds.), Springer-Verlag, Berlin ISBN 3-540-18178-4.

- V. V. Filippov, On the inductive dimension of the product of bicompacta, Soviet. Math. Dokl., 13 (1972), N° 1, 250-254.

- A. R. Pears, Dimension theory of general spaces, Cambridge University Press (1975).